In this chapter, we covered a lot of material that, at times, might not have been obvious. However, it is vital that you understand these issues.

For example, if you were not aware of the statement-level restart, you might not be able to figure out how a certain set of circumstances could have taken place.

That is, you would not be able to explain some of the daily empirical observations you make. In fact, if you were not aware of the restarts, you might wrongly suspect the actual fault to be due to the circumstances or end-user error. It would be one of those unreproducible issues, as it takes many things happening in a specific order to observe.

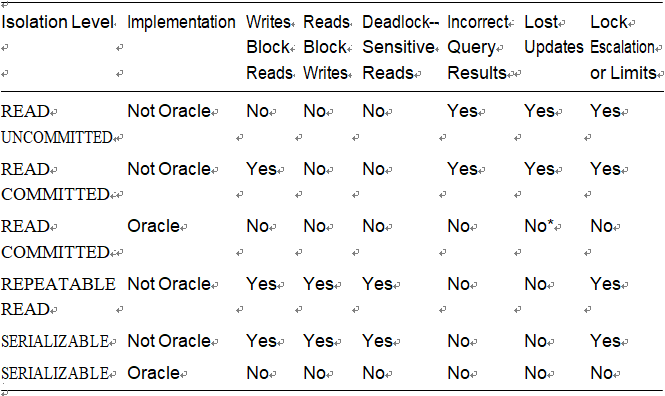

We took a look at the meaning of the isolation levels set out in the SQL standard and at how Oracle implements them; at times, we contrasted Oracle’s implementation with that of other databases.

We saw that in other implementations (i.e., ones that employ read locks to provide consistent data), there is a huge trade-off between concurrency and consistency. To get highly concurrent access to data, you would have to decrease your need for consistent answers.

To get consistent, correct answers, you would need to live with decreased concurrency. In Oracle, that is not the case, due to its multiversioning feature.

Table 7-9 sums up what you might expect in a database that employs read locking vs.

Oracle’s multiversioning approach.

Table 7-9. A Comparison of Transaction Isolation Levels and Locking Behavior in Oracle vs. Databases That Employ Read Locking

*With SELECT FOR UPDATE NOWAIT.

Concurrency controls and how the database implements them are definitely things you want to understand. I’ve been singing the praises of multiversioning and read consistency, but like everything else in the world, they are double-edged swords. If you don’t understand that multiversioning is there and how it works, you will make errors in application design. Unless you know how multiversioning works, you will write programs that corrupt data. It is that simple.